Error handling and raises

Gold can't be pure and man can't be perfect.

-- DAI Fugu 戴復古 (Song Dynasty)

It is not uncommon to encounter errors in programming. Errors are not necessarily bad, but failing to handle them properly can lead to unexpected behaviors and bugs in your code. That is why most programming languages provide mechanisms to handle errors gracefully.

Mojo, as a Python-like language, inherits the error handling mechanism from Python but makes it stricter. This chapter will introduce you to the error handling mechanism in Mojo, including:

- How to understand "errors" in Mojo

- A conceptual model that regards function results as blind boxes

- How to use the

raiseskeyword in function signatures - How to raise an error using the

raisekeyword - How to handle errors using the

tryandexceptkeywords - Why you should always explicitly propagate the error with additional context

Errors are just messages

Errors in Mojo are merely messages that the programmer want to convey to the users when a certain condition is met. They are not necessarily "wrong" or "bad", but rather a way to indicate that some operations are not allowed or undefined. The programmer will not make a decision for the users, but rather let them know that they need to handle the situation themselves. In this sense, errors are recoverable.

Since errors are not necessarily "wrong", some programmers may use the term "exceptions" instead of "errors". This word is semantically more neutral and does not imply any judgment about the situation. It simply indicates that something unexpected happened, and the users need to handle it. In this Miji, I use the term "errors", but these two terms can be used interchangeably.

One of the most common examples of errors is the "division-by-zero error". Dividing a number by zero is mathematically undefined, but not necessarily "wrong". Depending on the use cases, you may want to use a certain number to replace the result, you may want to return a "infinity" value, or you may want to just abort the program. In this sense, the programmer should not make a decision for the users, but pass a message to the users that "this operation is undefined mathematically, please handle it and pick a solution that fits your use case".

This is the core philosophy of error handling in Mojo: not about "catching" errors and "fixing" them, but rather about letting the users know that something is not right and they need to handle it themselves. If they do not handle it, the program will abort with the message that the programmer has provided.

The error messages in Mojo are represented by the built-in Error type, which is actually composed of a pointer to a string and the length of it. If you are interested, you can check the source code of the Error struct in the Mojo standard library.

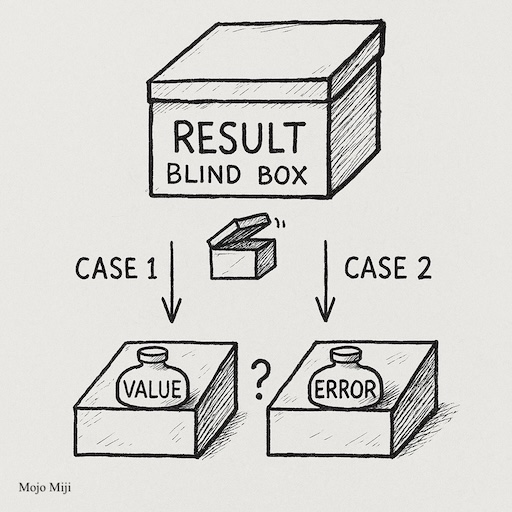

Result is a Blind Box

We all know that any function in Mojo has a return type. Even though it does not seem to return anything, it still returns a None type.

However, things become different when it comes to errors. When a function may generate an error, calling the function would result in two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: The error is not triggered, and the function returns a value of the expected type which is consistent with the function signature.

- Scenario 2 The error is triggered. The function does not return the expected type, but rather passes the error message back to the caller.

For example, the following function divide() takes two integers and returns their division result as an integer. Note that when the second argument is zero, the function passes an error message to the user, indicating that division by zero is not allowed.

# src/basic/errors/unhandled_error.mojo

def divide(x: Int, y: Int) -> Int:

if y == 0:

raise Error("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

def main():

var div1 = divide(10, 2)

print("10 // 2 =", div1)

var div2 = divide(10, 0)

print("10 // 0 =", div2)Running the above code will produce the following output:

10 // 2 = 5

Unhandled exception caught during execution: Cannot divide by zeroThe outcome of the above code shows the two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: The first call to

divide()works as expected and returns the result5as anInt, which is consistent with the function signature. - Scenario 2 The second call to

divide()triggers an error because the second argument is zero. The function does not return anInttype, but rather raises anErrorwith the message "Cannot divide by zero".

Therefore, we need to re-think about the conceptual model of the functions that may raise errors. These function does not simply return the expected type, but rather returns either the expected type or an Error type. It is a blind box that may contain either a value an error. You have to open the box to find out what is inside, just like what is shown in the following illustration:

Thinking in this way, we can write the function signature of divide() as follows:

# This is a pseudo-code, not valid Mojo code

def divide(x: Int, y: Int) -> ResultBox[Int, Error]:

if y == 0:

return Error("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // yThat is to say, the function divide() returns a container type ResultBox that can be either an Int or an Error, but not simultaneously. We will not know which one it is until you run the code (so the box is opened). And we have to handle both cases properly beforehand to avoid any surprises.

To return a container type like ResultBox allows the users to quickly understand that a function may raise an error. It also drives the users to handle the error more actively. Some programming languages, such as Rust, use a similar approach to handle errors. Python, on the other hand, does not make this information explicit. You would never know whether a function will raise an error or not until you run the code or read the documentation.

raises in function signature

Mojo, as a Python-like language, inherits most of the syntax style from Python. It does not wrap the errors in a container as a returned type. However, it still tries to make the errors more explicit by using the raises keyword in the function signature when you define the function with the fn keyword. This keyword explicitly indicates that the function may raise an error, the users should be aware of it and handle it properly.

The raises keyword is placed before the return type. If a function does not return anything (None), the signature is located at the end of the signature. A general function signature with the raises keyword looks like this:

fn foo(arg: Type) raises -> ReturnType:

...

fn foo(arg: Type) raises:

...As we have seen in Chapter Functions, the only difference between a fn function and a def function is that the fn function requires you to explicitly use the raises keyword in the function signature, where the def function does not. That is way in the example above, we did not use the raises keyword in the function signature of divide, because it is defined with def.

In case we use the fn keyword to define the divide function, the example should be written as follows:

# src/basic/errors/unhandled_error_with_raises_keyword.mojo

fn divide(x: Int, y: Int) raises -> Int:

if y == 0:

raise Error("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

fn main() raises:

var div1 = divide(10, 2)

print("10 // 2 =", div1)

var div2 = divide(10, 0)

print("10 // 0 =", div2)The function signature tells the users that the function divide may either return an Int type or return (raise) an Error type.

Raise an error

Because an error is just a potential outcome of a function, you need a keyword to pass it back to the caller but also differentiate it from the normal return value. In Mojo, you can use the raise keyword to indicate that the returned value is an error. Then caller must handle it properly, otherwise the program will abort with the error message.

| Keyword | Type | Behavior |

|---|---|---|

raise | Error | Pass an error from a function to the caller. The caller has to handle it to avoid program abort. |

return | Any type | Used to pass a value from a function to the caller. No need to handle it. |

Similar to the return keyword, when the program reaches the line with the raise keyword, the function will immediately stop executing and return to the caller. However, there is one exception:

If the raise keyword is used in the except block, the error is temporarily held. The program will first run the finally block and then re-raise the error to the caller.

Since Error is a also a valid Mojo type, you can also return an Error type using the return keyword. However, when you do so, Mojo will not treat it as an error, but rather as a normal return value. If you do not handle it, the program will not abort. See the following example:

fn return_error() -> Error:

return Error("This is an error message")

fn main():

try:

print(return_error())

print("No exception raised")

except e:

print("Caught an error:", e)Running the above code will produce the following output:

This is an error message

No exception raisedIn this example, the try block does not catch any exception because the return_error function does not raise an error, but rather returns an Error type as a normal return value. The program continues to run and prints "No exception raised".

Note that the Mojo compiler will also find out that no error is raised by the return_error function, and it will print some warning messages that the except block is unreachable:

warning: 'except' logic is unreachable, try doesn't raise an exception

print("Caught an error:", e)

^

warning: variable 'e' was never used, remove it?

except e:

^You may then ask, is it possible to use the raise keyword with a normal return type (not Error), e.g., raise SomeType?

The answer is: it is possible.

Recall that the raise keyword is used to pass an error message back to the caller. A message is naturally a text (string). Thus, when you run raise SomeType, Mojo will try to convert <some_type> to an Error type. If it is possible, then it will raise an error with the converted value. Let's see an example:

# src/basic/errors/raise_a_string.mojo

fn raise_type() raises:

var x = String("I am a string type")

raise x # Raise an error with a string type

fn main() raises:

raise_type()This will output:

Unhandled exception caught during execution: I am a string type

error: execution exited with a non-zero result: 1This means that the raise keyword successfully converts the String type to an Error type and passes it back to the caller. The program aborts with the error message "I am a string type".

Handle errors

When a function may raise an error, the caller must handle it properly. Otherwise, the program will abort with the error message. In Mojo, you can use the try-except-else-finally statements to handle errors. The syntax is similar to Python, which goes as follows:

- The

tryblock contains the code that may raise an error, either by calling a function that may raise an error or by using theraisekeyword directly. AnErrortype is expected to be raised in thetryblock. Once an error is encountered, the program will immediately jump to theexceptblock, skipping any code that follows in thetryblock, including other possible errors. - The

exceptblock contains the code that handles the error raised in thetry. You can either return a normal value, or you can propagate the error to the caller by using theraisekeyword again, or you can raise a new error with a different message. - The

elseblock is optional and contains the code that is executed when no error is raised in thetryblock. Otherwise, theelseblock will be skipped. You can also give a variable name after theexceptkeyword to store theErrorinstance raised in thetryblock, which can be used to access the error message. - The

finallyblock is also optional and contains the code that is always executed, regardless of whether an error is raised or not. It is often used for cleanup operations, such as closing files or releasing resources.

The complete syntax and the logic can be visualized as follows:

try:

# block of code that may raise an error

# the error is either raised by the function

# or by the `raise` keyword

<statements>

<call a function that may raise an error>

#

# If AN ERROR is raised,

# the following statements will not be executed

# the code will jump to the `except` block ────────────────┐

# │

# If NO ERROR is raised, │

# the following statements will be executed │

<statements> # │

# The code will jump to the `else` block ──────────────┐ │

except variable_name: # │ │

# block of code that handles the error │ │

# that is raised in the `try` block │ │

<statements> # ←─────────────────────────────────────────┼───┘

# The code will jump to the `finally` block ───────┐ │

else: # Optional │ │

# block of code that is executed when │ │

# no error is raised in the `try` block │ │

<statements> # ←─────────────────────────────────────┼───┘

# The code will jump to the `finally` block ───┐ │

finally: # Optional │ │

# block of code that is always executed │ │

# regardless of whether an error is raised or not │ │

<statements> # ←─────────────────────────────────┴───┘Let's see a concrete example of how to use the try-except-else-finally statements to handle the division-by-zero error in the divide() function we defined earlier. If the second argument is zero, we will use 0 as the result. The code looks like this:

# src/basic/errors/handle_errors.mojo

fn divide(x: Int, y: Int) raises -> Int:

if y == 0:

raise Error("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

fn main() raises:

var a = 10

var b = 0

var result: Int

try:

print("`try` branch - Before calling the `divide()` function")

result = divide(a, b)

print("`try` branch - If this line is reached, no error occurred")

except error_message:

print(

"`except` branch - Error occurred with the message:", error_message

)

print("`except` branch - Let's set the result to be 0")

result = 0

else:

print("`else` branch - No errors occurred, result is:", result)

finally:

print("`finally` branch - No matter what, this block will execute")

print(a, "//", b, "=", result)# src/basic/errors/handle_errors.py

def divide(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y == 0:

raise Exception("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

def main():

a = 10

b = 0

result: int

try:

print("`try` branch - Before calling the `divide()` function")

result = divide(a, b)

print("`try` branch - If this line is reached, no error occurred")

except Exception as error_message:

print("`except` branch - Error occurred with the message:", error_message)

print("`except` branch - Let's set the result to be 0")

result = 0

else:

print("`else` branch - No errors occurred, result is:", result)

finally:

print("`finally` branch - No matter what, this block will execute")

print(a, "//", b, "=", result)

main()Running the above code will produce the following output:

`try` branch - Before calling the `divide()` function

`except` branch - Error occurred with the message: Cannot divide by zero

`except` branch - Let's set the result to be 0

`finally` branch - No matter what, this block will execute

10 // 0 = 0The program successfully run without aborting, and the error is handled properly. Let's analyze the code step by step:

- The

tryblock is executed first. It calls thedivide()function withaandbas arguments. Sincebis zero, the function does not return a value, but rather raises an error with the message "Cannot divide by zero". The program immediately jumps to theexceptblock, skipping any code that follows in thetryblock. Thus, the print function is not executed. - The

exceptblock is executed next. TheErrorinstance raised in thetryblock is caught and stored in the variableerror_message. The program prints this error message and sets theresultvariable to0, which is of the expected typeInt. - The

elseblock is skipped because an error is raised in thetryblock. - The

finallyblock is executed regardless of whether an error is raised or not. It prints a message indicating that this block will always execute. - After the

try-except-else-finallystatements, the program prints the final result of the division operation, which is0.

Let's see what happens when the second argument of the divide() function is not zero. The code looks like this:

# src/basic/errors/handle_errors_another_example.mojo

fn divide(x: Int, y: Int) raises -> Int:

if y == 0:

raise Error("Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

fn main() raises:

var a = 10

var b = 2

var result: Int

try:

print("`try` branch - Before calling the `divide()` function")

result = divide(a, b)

print("`try` branch - If this line is reached, no error occurred")

except error_message:

print(

"`except` branch - Error occurred with the message:", error_message

)

print("`except` branch - Let's set the result to be 0")

result = 0

else:

print("`else` branch - No errors occurred, result is:", result)

finally:

print("`finally` branch - No matter what, this block will execute")

print(a, "//", b, "=", result)Running the above code will produce the following output:

`try` branch - Before calling the `divide()` function

`try` branch - If this line is reached, no error occurred

`else` branch - No errors occurred, result is: 5

`finally` branch - No matter what, this block will execute

10 // 2 = 5The program successfully run without aborting, and the result is calculated correctly. Let's analyze the code step by step:

- The

tryblock is executed first. It calls thedivide()function withaandbas arguments. Sincebis not zero, the function returns a value of5, which is of the expected typeInt. The program continues to execute all the code in thetryblock, including the print function. - The

exceptblock is skipped because no error is raised in thetryblock (the blind box is opened and contains a value of the expected type). - The

elseblock is executed next. It prints the result of the division operation, which is5. - The

finallyblock is executed regardless of whether an error is raised or not. It prints a message indicating that this block will always execute. - After the

try-except-else-finallystatements, the program prints the final result of the division operation, which is5.

You can see from the example that the try-except-else-finally statements provide a powerful way to handle errors in Mojo. Let's use the metaphor of the blind box again. The try block is where you open the box and take a look inside. If you find an okay value of the expected type, you continue with the remaining try block, the else block, and the finally block. If you find an error, you jump to the except block to handle it, and then continue with the finally block.

Mojo does not support multiple types of errors yet

You may have noticed that in the above examples, the syntax of except block in Mojo is slightly different from that in Python. In Python, you can specify the type of error you want to catch in the except block, such as except ValueError as e:, except OverflowError as e:, except ZeroDivisionError as e:, etc. This allows you to handle different types of errors differently.

On contrary, in Mojo, you cannot specify the type of error in the except block. This is because Mojo only has one built-in error type, which is the Error type. All errors raised in Mojo are of this type.

In the future, Mojo may support different types of errors and allow your to define your own error types. This will allow you to specify the type of error in the except block, just like in Python.

Raise an error in the except block

In the previous examples, we handled the error in the except block by setting the result to 0. But you do not have to do that. You can also choose to:

- Propagate the error to the caller by using the

raisekeyword again. In this way, you put the error back into the blind box and handle (or not handle) it in future. - Raise a new error with a different message. In this way, you can provide more context to the error and make it easier for the users to understand what went wrong.

Let's see how to propagate the error while adding more context to the error message with an example. We will define a new function area_when_radius_is_ratio() that calculates the area of a circle when the radius is given as a ratio of two numbers, i.e.,

The code looks like this:

# src/basic/errors/propagate_errors.mojo

fn divide(x: Float64, y: Float64) raises -> Float64:

if y == 0:

raise Error("Error in `divide()`: Cannot divide by zero")

else:

return x // y

fn area_when_radius_is_ratio(a: Float64, b: Float64) raises -> Float64:

var pi: Float64 = 3.14159

var radius: Float64

try:

radius = divide(a, b)

except e:

var new_error = Error(

"\nError in `area_when_radius_is_ratio()`: The radius is not a"

" valid ratio\nTraced back: "

+ String(e)

)

raise new_error

return radius**2 * pi

fn main() raises:

print(

"This program calculates the area of a circle when the radius equals"

" a / b"

)

var a = Float64(input("Enter the value for a: "))

var b = Float64(input("Enter the value for b: "))

print("The area =", area_when_radius_is_ratio(a, b))Running the above code with a = 10 and b = 0 will produce the following output:

This program calculates the area of a circle when the radius equals a / b

Enter the value for a: 10

Enter the value for b: 0

Unhandled exception caught during execution:

Error in `area_when_radius_is_ratio()`: The radius is not a valid ratio

Traced back: Error in `divide()`: Cannot divide by zeroLet's first analyze the logic of the code step by step:

- The

main()function calls thearea_when_radius_is_ratio()function withaandbas arguments to calculate the area of a circle with a radius equal to. - This function calls the

divide()function to get the radius. Sincedivide()may raise an error, we wrap the call in atryblock. The result of the division is stored in theradiusvariable. - If the second argument

bis zero, thedivide()function raises an error of theErrortype. This error instance is caught by theexceptblock.- We store the error instance in the local variable

e. - We create a new error instance with the name

new_error, which contains the original error message and some additional context about where the error occurred. - We raise the new error to the caller using the

raisekeyword.

- We store the error instance in the local variable

- At the end of the

area_when_radius_is_ratio()function, we return the area of the circle using the formula, where is the radius. - There will be two possible outcomes of the

area_when_radius_is_ratio()function:- If the second argument

bis not zero, the function will return aFloat64value. - If the second argument

bis zero, the function will raise aErrorinstance.

- If the second argument

- The

main()function does not handle the error raised by thearea_when_radius_is_ratio()function, so the program will abort in case of an error.

Then let's analyze the output step by step:

- Because

b = 0, thedivide()function raises an error instead of an okay value of the expected type. - The error is caught by the

exceptblock in thearea_when_radius_is_ratio()function. - Instead of handling the error by setting a default value, we create a new error instance with additional context about where the error occurred plus the original error message. This new error is raised to the caller.

- Since the

main()function does not handle the error, the program aborts with the error message.

Always explicitly propagate the error

Let's look at the error message in this example again:

Unhandled exception caught during execution:

Error in `area_when_radius_is_ratio()`: The radius is not a valid ratio

Traced back: Error in `divide()`: Cannot divide by zeroYou can see from the message that propagating the error with additional context can help the users understand what went wrong and where the error occurred. The users can simply use this information to quickly trace back every layer of the function calls back to the original error.

Mojo, unlike some other language, does not require you to explicitly handle the error with try-except statements. If you do not handle the error, the program will simply propagate the error to the next layer of the function calls.

However, this does not mean that you should ignore the error. Not handling the error may cause it difficult for the users find out the source of the error when the program aborts, especially when there are multiple layers of function calls involved.

For example, the following error message is definitely worse than the previous one:

Unhandled exception caught during execution: Cannot divide by zeroThis message does not provide any context about where the error occurred or what went wrong. The users may have to dig into the code to find out the source of the error. For larger projects, this can be a time-consuming and frustrating process.

To facilitate the debugging process, it is a good practice to always explicitly propagate the error with additional context in the except block. This way, you can provide more information about where the error occurred and what went wrong, making it easier for the users to understand and fix the issue.