Variables

Taiji (☯) generates two Yi's (⚊ ⚋); the two Yi's generate four Xiang's (⚌ ⚍ ⚎ ⚏); the four Xiang's generate eight Gua's (☰ ☱ ☲ ☳ ☴ ☵ ☶ ☷).

-- Yi-Jing (I Ching)

A variable is a fundamental concept in programming which allows you to store, read, and manipulate data. It can be seen as a container of data, enabling you to refer to the data by a symbolic name rather than the value in the memory directly. This is essential for writing readable and maintainable code. In this chapter, we will explore the following topics:

- Conceptual model of Mojo variables and two perspectives

- Python variables vs Mojo variables

- Creation of variables

- Re-assignment of variables

- Assignment of values between variables

- Scope of variables

Conceptual model of Mojo variables

There are various way to define the term "variable", and the definition varies across programming languages. In this Miji, I would provide the following conceptual model which I found easy to understand and remember when I program in Mojo:

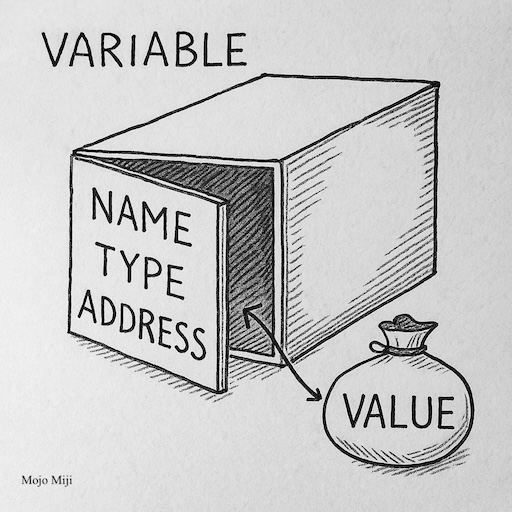

A variable in Mojo is a quaternary system consisting a name, a type, an address, and a value.

- The name of the variable is the unique identifier that you use to refer to the variable in your code.

- The type of the variable defines what kind of data it can hold, how much memory space it occupies, how it can be manipulated, and how the value is represented in binary format in memory.

- The address of the variable defines where the data is stored in memory.

- The value of the variable is a meaningful piece of information that you directly or indirectly create or use. It is usually stored in a binary format in the memory.

This conceptual model is rather abstract. To facilitate understanding, we can further view Mojo variables from two different perspectives: an object-oriented perspective and a safe-vault perspective. The first perspective is more Pythonista-friendly, focusing on the relationship between the variable name and the object; the second perspective is more low-level, focusing on how the values are stored and transferred in memory. We will explore both perspectives in the following sections.

Object-oriented perspective

As a Pythonista, you may be more comfortable with understanding everything from a object-oriented perspective. Good news is that we can definitely do this for Mojo's variables as well. Let's start by defining a Mojo object

A Mojo object is an abstract object in memory with three attributes:

- Type

- Address.

- Value

For example, the integer 1 is a Mojo object with type Int, value 1, and an address in memory (let's say, 0x26c6a89a). The string "Hello, world!" is another Mojo object with type String, value "Hello, world!", and another address in memory (let's say, 0x26c6b00f).

Then, a Mojo variable can be defined as a mapping from a name to an object. More intuitively, the variable name is a label that is stuck onto a Mojo object. See the following illustration:

# Mojo Miji - Basic - Variables - Mojo variables and objects

variable name

↓

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ Mojo object (abstract) │

├──────────┬─────────┬───────────┤

│ type │ value │ address │

└──────────┴─────────┴───────────┘This approach is consistent with the quaternary system introduced above. The only difference is that we view the type, value, and address together as an abstract object, which is an extra layer of abstraction.

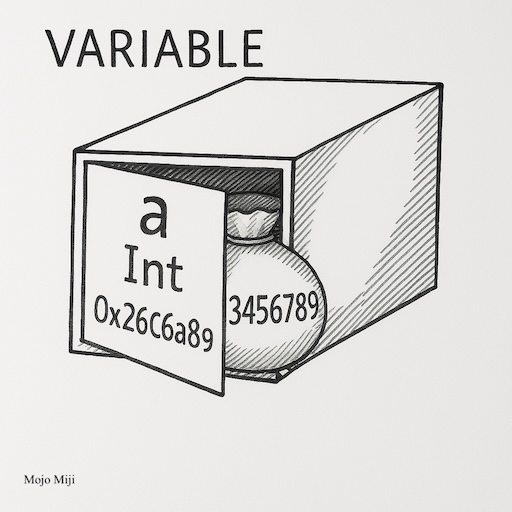

Value-vault perspective

Another way to understand a variable is to view it from a low-level, memory-oriented perspective. Let's start by defining a value vault

A value vault is an abstract safe vault with three attributes:

- Name

- Type

- Address

The safe vault is located at the address and is immovable. The type defines how much space the vault occupies in memory and how the value is represented in binary format in memory. The name is a label stuck onto the vault, allowing you to refer to the vault in your code.

Then, a Mojo variable can be defined as a Safe vault with a value inside. The value is stored in the vault in a binary format according to the rules defined by the type. See the following illustration:

This approach is more value-oriented and memory-oriented. It emphasizes how the values are stored and transferred in memory, which is crucial for understanding concepts like ownership, mutability, and memory safety in Mojo.

A concrete example of a variable

Both the object-oriented perspective and the safe-vault perspective are useful for understanding Mojo variables, and they are consistent with the quaternary system introduced above. You can choose either one according to your preference.

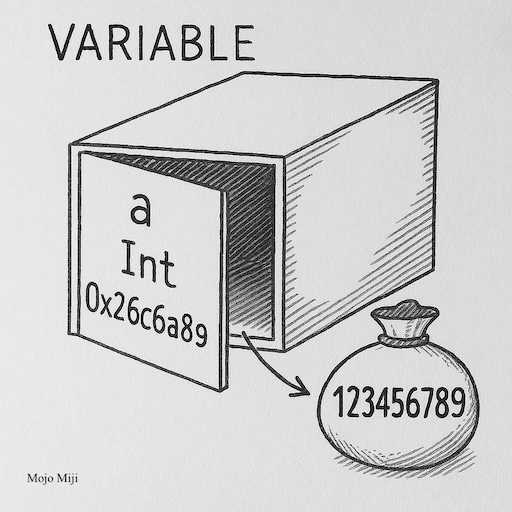

Now, let's take a look at a concrete example of a variable in Mojo and how it is laid out in memory:

The variable is of name a, of type Int, of address 0x26c6a89a, and of value 123456789. Since the Int type is 64-bit (8-byte) long, it actually occupies the space from 0x26c6a89a to 0x26c6a8a1. The value 123456789 is stored in the memory space in a binary format, which is 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000101 00000101 (in little-endian format).

So the memory layout of the variable a can be illustrated as follows:

# Mojo Miji - Basic - Variables

local variable `a` (Int type, 64 bits or 8 bytes)

↓ (stored on stack at address 0x26c6a89a in little-endian format)

┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

Name │ a │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

Type │ Int │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

Value │ 123456789 │

├──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┤

Value (binary) │ 00000000 │ 00000000 │ 00000000 │ 00000000 │ 00000111 │ 01011011 │ 11001101 │ 00010101 │

├──────────┼──────────┼──────────┼──────────┼──────────┼──────────┼──────────┼──────────┤

Address │0x26c6a89a│0x26c6a89b│0x26c6a89c│0x26c6a89d│0x26c6a89e│0x26c6a89f│0x26c6a8a0│0x26c6a8a1│

└──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┘If we view the variable from the object-oriented perspective, then it is a mapping from the name a to a Mojo object. The object is of type Int, value 123456789, and address 0x26c6a89a. See the following illustration:

# Mojo Miji - Basic - Variables

variable name: a

↓

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Mojo object (abstract) │

├───────────┬──────────────────┬─────────────────────┤

│ type: Int │ value: 123456789 │ address: 0x26c6a89a │

└───────────┴──────────────────┴─────────────────────┘If we view the variable from the safe-vault perspective, then it is a immovable safe vault with name a and type Int at address 0x26c6a89a, and it contains the value 123456789. See the following illustration:

Always apply the conceptual model

When you program in Mojo, you should always apply the conceptual model and view a variable as a system consisting of four aspects, a name, a type, an address, and a value. In this way, you can better understand how variables are interacted with each other. When you step into the concept "ownership", it will save you a lot of effort to understand it.

For example, when you initialize a variable, you are doing the following things:

- Specify the type of the variable.

- Ask for an address, a memory space, to properly store the data.

- Store the value in the memory space in a binary format.

- Select an name for the variable.

When you use a variable via its name, you are doing the following four things:

- Find out the information of the variable in the symbol table, which includes its name, type, and address in the memory.

- Go to the memory address to retrieve the value stored there.

- Interpret the value according to its type.

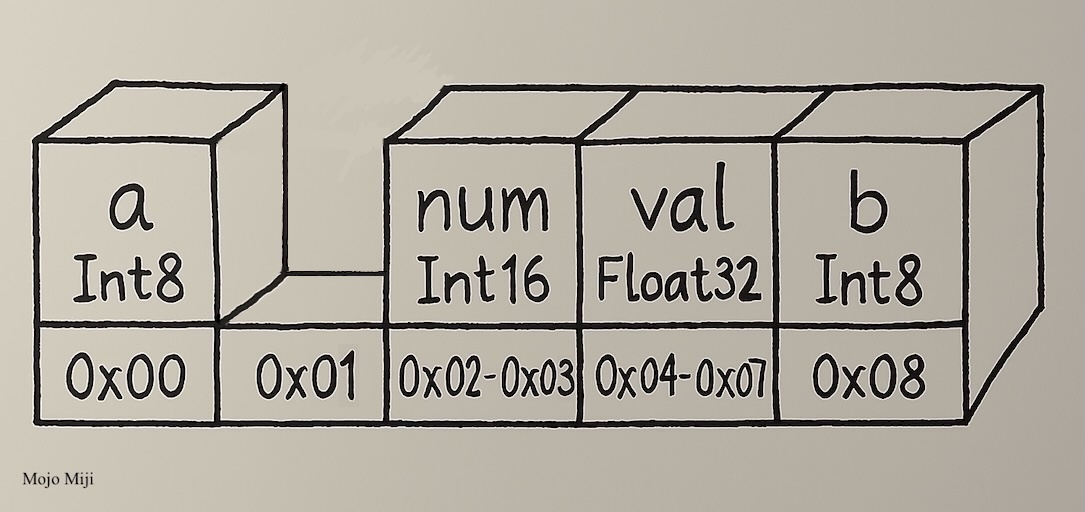

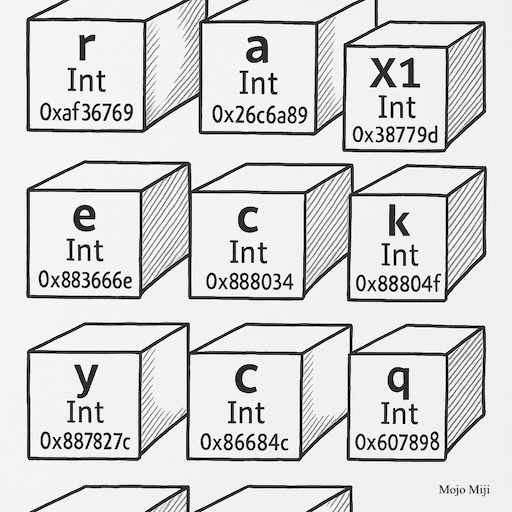

There can be many, many variables in a program. They will be stored in different locations in the memory, each with its own name, type, address, and value. The following figure shows a few variables (as safe vaults) in a program. Note that some vaults are bigger than others and occupy more space in the memory. Some addresses are not yet occupied by any vaults.

Type is important

The values of variables stored in the computer's memory is not in a human-readable format. For example, the value 12.5 does not appear as "12.5" if you use a microscope to look into your computer's RAM stick. Physically, the memory is a sequence of units with binary, mutually exclusive states, which can be represented as 0 and 1 (or, yes and no, sun and moon, yīn and yáng...), e.g., 00000000 00001100 00000000 00001101... These units are called bits.

How to interpret these bits into a human-readable format? It depends on the type of the variable. There are pre-defined rules for each type to interpret the bits into a human-readable value, or translate a human-readable value into bits. For example, if the value in bit format is 0000000000000010 and the type is Int8, then it is interpreted as the integer 2. For the same value 0000000000000010, if the type is Float16, then it is interpreted as a floating-point number 0.00000011920928955078125. Certain manipulations can only be performed on certain types of variables. You can not apply a method that is defined for Int on a variable of type String.

In short, the type of a variable is very important as it defines how the program interprets and manipulates the data.

Python variables vs Mojo variables

Conceptual model of Python variables

In Python, a variable is a name that refers to an object in memory. The object itself contains the type information and the value. The memory layout and the location of the object are not directly accessible, but are abstracted away from the user. Each object has a unique identifier (which can be obtained using the built-in id() function), but this identifier is not the same as a memory address and should not be relied upon for memory management.

Thus, the conceptual model of a variable in Python can be simplified as the following system:

- name: a human readable name that is associated with the object

- object: an abstract object in memory with three attributes:

- type of the object

- value of the object

- unique ID of the object

See the following abstract representation of a variable in Python:

# Mojo Miji - Basic - Variables - Python variables

variable name

↓

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Python object (abstract) │

├──────────┬─────────┬────────┤

│ type │ value │ ID │

└──────────┴─────────┴────────┘At a glance, this quaternary system is very similar to that of Mojo's variable, except for that the "address" in Mojo is replaced by "unique ID".

However, in Python, the type, value, and unique ID are so tightly coupled together as an object that they cannot be separated. And, in most cases, you cannot directly manipulate the values of the object and you cannot even destroy an object manually. You can only manipulate the name and the relationship between the name and the object.

The fact that Python's object is a well-encapsulated black box is the key to understand the fundamental difference between the behavior of Python variables and Mojo variables that we will encounter in the future throughout this Miji.

Here are some concrete examples for you to understand Python variables more intuitively.

1984 by George Orwell can be seen as an object. It has a type (book), a value (the content of the book), and a unique identifier (ISBN number). The variable name in Python is like a sticker with the name "my favorite book" that you stick onto the book cover. You can then use the name "my favorite book" to refer to the book object. As such, the binary system of the name "my favorite book" and the book object is a variable in Python.

You can also stick another sticker with the name "best_seller" onto the same book. Now you have two names referring to the same object.

Macbook Pro 2025 can be seen as another object. It has a type (laptop), a value (the hardware and software configuration of the laptop), and a unique identifier (serial number). You can stick a sticker with the name "my laptop" onto the laptop cover. Now you have a variable in Python consisting of the name "my laptop" and the laptop object.

Of course, you can also stick other stickers with different names onto the same laptop object.

Construction, re-assignment, and use of Python variables

Now, let's apply the conceptual model to understand how Python variables are created, re-assigned, and used. A sample code is as follows:

a = 1

b = a

c = b

print(a is b)

a = "Hello world!" # `a` is stuck onto a string object with value `"Hello world!"`

print(a, b, c)

del b

print(c)Let's analyze the code line by line.

When you create a variable in Python, e.g., a = 1, Python actually does the following things:

- Internally create an object in the memory with the value

1, typeint, and a unique identifier (let's say,140703303123456). - Create a label with the name

aand stick it onto the object.

When you do b = a, Python does the following things:

- Find the object with the name

ain the memory. - Create another label with the name

band stick it onto the same object. Note that there are now two labels (aandb) on the same object.

When you do c = b, Python does the following things:

- Find the object with the name

bin the memory. - Create another label with the name

cand stick it onto the same object. Note that there are now three labels (a,b, andc) on the same object.

When you do print(a is b), Python checks whether the two labels a and b refer to the same object in memory. Since they do, it prints True.

When you do a = "Hello world!", Python does the following things:

- Internally create a new object in the memory with the value

"Hello world!", typestr, and a unique identifier (let's say,140703303654321). - Remove the label

afrom the first object (with typeintand value1) and stick it onto the new object (with value"Hello world!"). Note that the labelsbandcare still stuck onto the first object.

When you do print(a, b, c), Python retrieves the values of the objects that the labels a, b, and c refer to, and prints them. It prints "Hello world!" 1 1.

When you do del b, Python removes the label b from the first object. Now only the label c is stuck onto the first object.

When you do print(c), Python retrieves the value of the object that the label c refers to, and prints it. It prints 1.

What do we learn from this example?

- In Python, we do not directly manipulate the objects in memory. We only manipulate the labels (variable names) and the relationship between labels and objects.

- The objects themselves are hidden from us. We do not need to know where they are stored in memory, how much space they occupy, or how they are represented in binary format.

- Change the value of a variable (re-assignment) does not necessarily change the object itself. It may create a new object and change the label to refer to the new object.

delstatement only removes the label from the object but does not delete the object itself. The object will be automatically deleted by Python's garbage collector when there are no more labels stuck onto it.

Mojo objects are directly manipulated

Now we can see the fundamental difference between Python variables and Mojo variables: Mojo can directly manipulate the value of the variable at the a specific memory location, while Python only manipulates the labels (variable names) and the relationship between labels and objects.

As I said before, a Mojo variable is associated with a memory address. When you do a = 1, the variable a will be associated with a type Int, a value 1, and an address in memory. When you do a = 2, the variable a will still be associated with the same address in memory, but the value will be changed to 2 (physically, the state of the electrons at that location changed). You can never do a = "Hello world!" because the type of a is Int, and you cannot insert a string value into that address.

In other words, the Mojo variable name is a sticker stuck onto a physical memory address directly, while the Python variable name is a sticker stuck onto an abstract object in memory.

In the later chapters, we will continue to see how this difference affects the way we assign values between variables.

Major difference between Python variables and Mojo variables

Here is a quick glance of some major differences between Python variables and Mojo variables that are resulted from the different conceptual models. I will elaborate these differences in details later in this Miji.

- In Python, you can stick multiple stickers (variable names) onto the same object (of the same ID). Thus, multiple variable names can refer to the same object.

- In Mojo, you can only stick one sticker (variable name) onto one object (at a specific memory address). Thus, one variable name can only refer to one memory address.

- In Python, you cannot manually destroy an object. You can only remove the sticker (variable name) from the object. The object will be automatically destroyed by Python's garbage collector when there are no more stickers (variable names) stuck onto it.

- In Mojo, you can manually destroy a variable, which will free up the memory space occupied by the variable.

- In Python, you cannot directly manipulate the value of the object. If you re-assign a variable name to a new value, you are actually creating a new object and changing the sticker (variable name) to refer to the new object.

- In Mojo, you can directly manipulate the value of the variable at a specific memory location. If you re-assign a variable to a new value, you are changing the value stored at the same memory address.

- In Python,

b = ameans that you are creating a new sticker (variable nameb) and stick it onto the same object that variable nameais stuck onto. Thus, bothaandbrefer to the same object. - In Mojo,

b = ameans that you are copying the value of variableainto variableb. Thus,aandbrefer to different memory addresses and thus different objects.

Identifiers

Identifiers are names used to identify variables, functions, structs, classes, etc.

Mojo has the exactly the same rules for identifiers as Python does. You can always use your existing knowledge of Python identifiers in Mojo. To be more specific, Mojo has the following rules on identifiers:

- Identifiers must consist of letters (both uppercase and lowercase), digits, and underscores (

_), e.g,my_variable,MyVariable,my_variable_1,_temp_variable, etc. - Identifiers cannot start with a digit, e.g.,

1st_variableis not a valid identifier, butfirst_variableis. - Identifiers cannot be a keyword (reserved word), e.g,

if,for,while,def, etc. are not valid identifiers. - Identifiers are case-sensitive.

There is one feature that is new in Mojo. You can use the grave accent (``) to create an identifier that does not follow the rules above. For example, the following code is valid in Mojo:

# src/basic/variables/identifiers.mojo

def main():

var `var`: Int = 1

var `123`: Int = 123

print(`var`) # Using backticks to escape the keyword 'var'

print(`123`) # Using backticks to escape the numeric identifier '123'As what you may learn from Python, variables with prefixes like _ or __ have some special meanings. Mojo also adopts this convention. For example, variables with a single underscore prefix (e.g., _temp) are considered private or temporary variables, and users should not access them directly (like private keywords in other languages). Variables with a double underscore prefix (e.g., __temp) are considered private to the classes or structs. Particularly, variables with double underscores before and after the name (e.g., __init__) are considered special methods for classes or structs, which are called "double-underscore methods" or "dunder methods". These dunder methods provide an uniformed interface for system functions to work on different types, achieving polymorphism.

Create variables

Now we look into how to create a variable in Mojo with help of the the conceptual model and the figure introduced above.

Declare and initialize variables

In Mojo, the complete syntax to create a variable includes two steps:

- Declaration: The syntax is

var name: Type. Avarkeyword is followed by variable name and type. This tells Mojo compiler that a new variable with the specified name and type shall be created in the current code block (scope). Please allocates a memory space for the variable based on its type. To declare a variable is also called to define a variable, as we have provide all information on the variable. - Initialization The syntax is

name = value. An equal sign is followed by a value. This tells Mojo compiler to store the value in the allocated memory space in a binary format. How to convert the value into binary format depends on the type of the variable. To initialize a variable is also called to assign a value to the variable.

In the syntaxes of these two steps:

varis the keyword to declare a variable.nameis the name of the variable, which must be a valid identifier.Typeis the type of the variable, which must be a valid Mojo type.valueis the value to put assigned to the variable, which must be a valid literal of the compatible types.

Some examples are as follows:

# src/basic/variables/variable_definition_assignment.mojo

def main():

# Define variables first

var a: Int

var b: Float64

var c: String

var d: List[Int]

# Assign values to the variable names in separate lines

a = 1

b = 2.5

c = String("Hello, world!") # c = "Hello, world!" is also valid

d = [1, 2, 3]# Python also allows you to give type hints to variables in separate lines

def main():

# Give type hints first (these lines are ignored by Python interpreter)

a: int

b: float

c: str

d: list[int]

# Assign values to the variable names in separate lines

a = 1

b = 2.5

c = str("Hello, world!") # c = "Hello, world!" is also valid

d = [1, 2, 3]

main()// This is similar in Rust

fn main() {

// Define variables first

let a: i64;

let b: f64;

let c: String;

let d: Vec<i64>;

// Assign values to the variable names in separate lines

a = 1;

b = 2.5;

c = "Hello, world!".to_string();

d = vec![1, 2, 3];

}The above two steps can be combined into one line, i.e., var name: Type = value. This means that the declaration and initialization take place at the same time. Let's re-write the above examples in this way:

# src/basic/variables/variable_creation.mojo

def main():

var a: Int = 1

var b: Float64 = 2.5

var c: String = "Hello, world!"

var d: List[Int] = [1, 2, 3]# Python also allows you to give type hints in the same line

def main():

a: int = 1

b: float = 2.5

c: str = "Hello, world!"

d: list[int] = [1, 2, 3]

main()// This is similar in Rust

fn main() {

let a: i64 = 1;

let b: f64 = 2.5;

let c: String = "Hello, world!".to_string();

let d: Vec<i64> = vec![1, 2, 3];

}The two ways of creating variables are equivalent. The second example is more concise and Pythonic. The first example is also useful when you want to show other people which variables will be used later. Which one is better depends on your personal preference and the purpose of the code.

Too verbose

You may find that the complete syntax of variable creation is still verbose, compared to Python. However, Yuhao still recommends you to always follow this complete style, as it is more explicit and error-free, especially the inlay hints is not yet supported by Mojo extension. Being confident is good, but being explicit is better.

The only exception, where you can omit the type annotation, is when you use the explicit constructors of types, such as var l = List[Int](1, 2, 3), var s = String("Hello"), or var i = Int128(100). In this case, the Mojo compiler can infer the type of the variable from the constructor.

If you still want to chill a bit, luckily, Mojo is more than "clever" to allow you to omit the var keyword as well as the type annotation and use a simplified syntax: name = value, just like Python. This will be discussed in details in a later section.

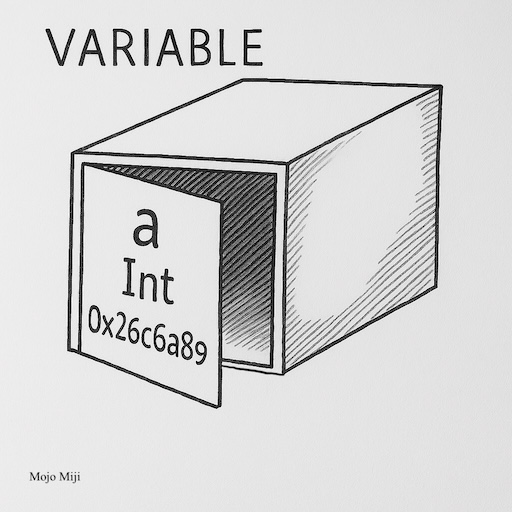

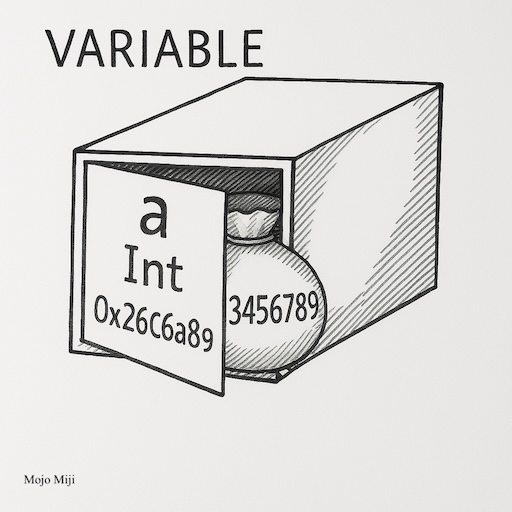

Initialized and uninitialized variables

If you declare a variable without assigning a value to it, we call that the variable is uninitialized. It is like that you buy a vault (with a name, a type, and an address printed on the door) but you do not put anything inside it. When you assign a value into the variable later, then we can say that the variable is initialized.

See the following two figures. If you declare a variable with var a: Int, then Mojo will create a space in the memory at the address 0x26c6a89a (for example). It is like that you buy a new vault without putting anything inside it. It is uninitialized.

When you use the syntax a = 123456789, then Mojo will store the value 123456789 in the memory space at the address 0x26c6a89a. It is like that you put the value 123456789 into the vault. Now the variable a is initialized.

The var keyword

Mojo uses the var keyword to declare a variable. This keyword is not required in Python.

var explicitly tells the Mojo compiler that you want to create a new variable and the name of the variable must be the first time appearing in the current code block (scope). This implies that you cannot use the var keyword twice for the same variable name in the same scope. For example, the following code will result in an error:

# src/basic/variables/redefinition.mojo

def main():

var a: Int = 1

var a: Int = 2 # We use `var` keyword again for variable name `a`error: invalid redefinition of 'a'

var a: Int = 2 # Error: invalid redefinition of 'a'

^Variable shadowing

Though not possible in Mojo, redefining a variable with the same name (even with a different type) is allowed in some other languages. This is called variable shadowing (or "redefinition"). For example, in Rust and Python, the following code is legal:

fn main() {

let a: i32 = 1;

let a: String = "Hello".to_string(); // Redefine variable `a` with a different type

}def main():

a: int = 1

a: str = "Hello" # Redefine variable `a` with a different type

main()But in Mojo, it is not allowed. I find this a good design choice, as it helps to avoid confusion and potential bugs caused by variable shadowing. If you want to change the type of a variable, please instead use a different name for the new variable.

Skip definition with var

When creating a new variable, you can optionally skip the definition part of the variable creation syntax, i.e., you can omit the var keyword and the type annotation, and directly assign a value to a variable. By doing so, Mojo will automatically define the variable for you. This is similar to how you do it in Python. For example, the following simplified syntax is valid in Mojo.

# src/basic/variables/variable_creation_without_var.mojo

def main():

a = 1

b = 2.5

c = "Hello, world!"

d = [1, 2, 3]# src/basic/variables/variable_creation_without_var.py

def main():

a = 1

b = 2.5

c = "Hello, world!"

d = [1, 2, 3]In this example, Mojo sees that you are assigning a value 1 to a undeclared variable a (Mojo sees this name for the first time). It knows that you want to create a new variable. So it will automatically declare the variable a with the type Int for you. The same applies to the other variables b, c, and d.

Some Pythonistas will be happy now. But remember, if you omit the var keyword, then you have to also omit the type annotation. In other words, if you want to use type annotations, you must use the var keyword. Note that the following code won't work:

# src/basic/variables/variable_creation_without_var_but_with_types.mojo

# This code will not compile

def main():

a: Int = 1

b: Float64 = 2.5

c: String = "Hello, world!"

d: List[Int] = [1, 2, 3]This is because type annotations are part of the variable definition, together with the var keyword. If you determine to skip the definition part, then you should also omit the type annotations.

let and var

Do you know that, in early versions of Mojo, the let keyword is used to declare immutable variables (just like in Rust) and the var keyword is used to declare mutable variables. From v24.4 (2024-06-07), the let keyword has been completely removed from the language. You can find relevant discussion in the following thread on GitHub:

From v24.5 (2024-09-13), the var keyword has also become optional, to be fully compatible with Python. However, many Magicians find this not a good move. In the following sections, you will see why.

Type annotations

Python is a dynamic, strongly-typed language. When we say that it is strongly-typed, we mean that Python enforces type checking at runtime and there are less implicit type conversions. When we say that it is dynamic, we mean that Python does not require you to declare the type of a variable before using it. You can assign any value to a variable, and Python will determine its type at runtime. From Python 3.5 onwards, Python also supports type hints, which allows you to annotate the types of variables and function arguments, but these are optional and do not affect the runtime behavior and performance of the code. Giving incorrect type hints will not cause any errors. The Python's type hints are primarily for static analysis tools and IDEs to help you catch potential errors before running the code, and it also helps other developers (or yourself in future) understand your code better.

Python's type hints are primarily for IDE static checks and readability, and are not mandatory, having no impact on performance[1].

In contrast, Mojo is statically compiled. Therefore, data types of variables must be explicitly declared so that the compiler can allocate appropriate memory space.

The syntax for type annotations in Mojo is var name: Type, where the type always follows the variable name with a colon :. This is similar to Python's type hints. Some early programming languages, like C or C++, use the syntax Type name to declare a variable.

Type inference

As mentioned above, Mojo compiler is smart enough to infer the type of variable based on the literals, expressions, and the returns of functions. Thus, you do not need to always provide type annotations when you create a variable. We will discuss this in detail in Chapter Literals and type inference.

Nevertheless, it is still recommended that you provide type annotations as much as you can for clarity and to avoid ambiguity, especially when you are not sure about the default types of literals or expressions.

For example, the following code is good because it will lead to no ambiguity:

# src/basic/variables/type_annotations.mojo

fn main():

var a: Float64 = 120.0 # Use type annotations for literals

var b: Int = 24 # Use type annotations for literals

var c = String("Hello, world!") # Use explicit constructors

var d = Int128(100) ** Int128(2) # Use explicit constructors

print(a, b, c, d)In an exercise in Chapter Types, we will see that absence of type annotations can sometimes lead to unintended behaviors.

Inlay hints

Some IDEs provides inlay hints that show the inferred types of variables. You can use it to check whether the compiler has inferred the data type correctly. For example, the Rust and Python extensions of Visual Studio Code provide inlay hints. Mojo does not yet provide this feature. Thus, I recommend you to always provide type annotations, particularly for literals.

Value re-assignment

Once a value is created, we can always change its value using equal sign =. This is called value re-assignment. The type of the variable must be compatible with the new value, otherwise, you will get a compilation error. For example, the following code is valid:

# src/basic/variables/reassign_values.mojo

fn main():

var a: Int = 1

a = 10Note that the following code is incorrect because a is of type Int and cannot be assigned a String.

# src /basic/variables/reassign_values_with_different_types.mojo

fn main():

var a: Int = 1

a = "Hello!"You can think of value re-assignment disposing the old value from the vault and putting a new value into the it. The name, type, and address printed on the door of the vault remain unchanged.

Use of variables

Once a variable is created, you can use it in your code by referring to its name. This is called using the variable. When you use a variable, the Mojo compiler will look up the symbol table to find the information of the variable. Then it will retrieve the value from the memory address.

This name-to-value mapping is straightforward. You do not need to use any extra syntax or operators. Just write down the name of the variable, and the compiler will find out the value for you.

You can think of this process with our previous metaphor as follows:

First, you provide the name of the vault (variable) to the Mojo compiler, let's say, a. The Mojo compiler will then look up the room and find the vault with the specified name a.

It is in the middle of the first row. The Mojo compiler opens the vault and retrieves the value stored inside it.

Assign values between variables

Recall that, in section Conceptual model of Python variables, we have discussed how variables in Python are fundamentally different from those in Mojo. This difference also affects how we assign values between variables.

In Python, we can use the syntax variable_b = variable_a to assign bind the name variable_b to the object that variable_a is referring to. In another word, if an object with ID 140703303123456 is referred to by the name variable_a, then after the assignment, it will be referred to by both names variable_a and variable_b. Thus, both names refer to the same object in memory. For example,

# src/basic/variables/assign_values_between_variables.py

def main():

a = 1 # `a` is now referring to an int object with value 1

b = a # `b` is now referring to an int object with value 1

print("a =", a)

print("b =", b)

print("id(a) = id(b):", id(a) == id(b))

str1 = "Hello" # `str1` is now referring to a string object with value "Hello"

str2 = str1 # `str2` is now referring to the same string object as `str1`

print("str1 =", str1)

print("str2 =", str2)

print("id(str1) = id(str2):", id(str1) == id(str2))

lst1: list[int] = [1, 2, 3]

# `lst1` is now referring to a list object with three integers

lst2: list[int] = lst1 # `lst2` is now referring to the same list object as `lst1`

print("lst1 =", lst1)

print("lst2 =", lst2)

print("id(lst1) = id(lst2):", id(lst1) == id(lst2))

main()The code will produce the following output:

a = 1

b = 1

id(a) = id(b): True

str1 = Hello

str2 = Hello

id(str1) = id(str2): True

lst1 = [1, 2, 3]

lst2 = [1, 2, 3]

id(lst1) = id(lst2): TrueIn Mojo, the syntax variable_b = variable_a would lead to a copy operation if the types are implicitly copyable. For now, you may think of implicitly copyable types as simple data types like integers, floating-point numbers, and strings.

Do note the difference here: in Python, both variable_a and variable_b refer to the same object in memory; in Mojo, the value of variable_a is copied to the memory location of variable_b. Thus, after the assignment, variable_a and variable_b refer to different memory locations with the same value.

For example:

# src/basic/variables/assign_values_between_variables.mojo

def main():

var a = 1 # Put the value 1 into the variable with name `a` and type `Int`

var b = a # Copy the value of `a` into the variable with name `b` and type `Int`

print("a =", a)

print("b =", b)

print(

"a and b has the same address:",

Pointer(to=a) == Pointer(to=b),

)

var str1: String = "Hello"

var str2 = str1

print("str1 =", str1)

print("str2 =", str2)

print(

"str1 and str2 has the same address:",

Pointer(to=str1) == Pointer(to=str2),

)The code will produce the following output:

a = 1

b = 1

a and b has the same address: False

str1 = Hello

str2 = Hello

str1 and str2 has the same address: FalseAs you can see, even though a and b have the same value, they are stored in different memory locations. The same applies to str1 and str2.

When in Mojo, do as Magicians do: be aware of the underground differences between Python and Mojo variables, and always remember that variable_b = variable_a means copying the value of variable_a into variable_b, not making them refer to the same object in memory.

Explicit copyable types

You may wonder why I did not mention lists in the above example. This is because lists are not implicitly copyable in Mojo. If you want to copy a list, you have to use the copy() method explicitly, like list_b = list_a.copy(). We will discuss this in detail in Chapter Copy, implicit copy, and move later.

Scope of variables

The scope of a variable is the region of code where the variable can be accessed. It is determined by the location where the variable is defined (or, declared). A typical code block is a function, a for loop, a while loop, an if statement, etc.

If you declare a variable inside a function, then the variable can only be accessed within that function. If you declare a variable inside a for loop, then the variable can only be accessed within that loop. See the following example that won't work:

# src/basic/variables/use_variables_of_sub_scopes.mojo

# This code will not compile

def main():

if True:

var a: Int = 1

print(a)

print(a) # This will cause an errorerror: use of unknown declaration 'a'

print(a) # This will cause an error

^This is because the variable a is declared inside the if statement and only accessible within that if statement. When the program goes out of the if statement, the variable a (name, type, address, and value) is dead, or destroyed. Therefore, when you try to access a in the second print(a), it cannot find the variable a anymore.

On the other hand, variables declared in the parent scope can be accessed in the child scope. For example, if you define a variable in a function, you can always assess this variable in a nested for loop inside that function. The code below will work:

# src/basic/variables/use_variables_of_parent_scopes.mojo

def main():

var a: Int = 1 # Declare a variable in the parent scope

print(a) # Access the variable `a` in the parent scope is valid

for _i in range(5): # for loop as a child scope

print(a) # Access the variable `a` in the child scope is validThe scope of a variable is also called its lifetime, which is a very important concept in Mojo. We will discuss it in detail in ChapterLifetime system of this Miji, which is about advanced features of Mojo.

Re-declaring variables in nested scopes

In the previous section, I mentioned that, if you declare a variable using the var keyword, it means that a variable is being created in the current code block (scope). Why we have to emphasize this? Because means that:

- You cannot use the

varkeyword to declare a variable with the name of an existing variable in the same scope (we have discussed this "shadowing" above). - However, you can still use the

varkeyword to declare a variable with the same name as an existing variable in a nested scope (child scope). See the following example:

# src/basic/variables/redeclare_variables_in_nested_scopes.mojo

def main():

var a: Int = 1

print("a =", a, " (before the if block)")

if a < 10:

var a: Float64 = 3.1415926

print("a =", a, " (inside the if block)")

print("a =", a, " (after the if block)")This code will work and produce the following output:

a = 1 (before the if block)

a = 3.1415926 (inside the if block)

a = 1 (after the if block)The reason is that, when you go into a nested scope (child code block), the Mojo compiler allows you to overwrite the variable name in the parent scope. And the overwritten variable only exists in the child scope. When you go out of the child scope, the variable in the parent scope is still there, and you can access it again. In the above example,

- You first define a variable

aof typeIntand value1in themainfunction. - Then, you enter the

ifblock and declare a new variableaof typeFloat64and value3.1415926. This new variable shadows the original variableain the parent scope. Mojo compiler will allocate new memory space for this new variable, while keeping the memory space of the original variableain the parent scope intact. When you printainside theifblock, it refers to the new variable with value3.1415926. - Next, you go out of the

ifblock, and the new variableais destroyed. The original variableain themainfunction is still there. When you printaoutside theifblock, it refers to the original variable with value1.

How is this possible? The Mojo compiler will always keep track of the variable names in different scopes. This means that the true, internal name of a variable is actually a combination of its name and the scope it is defined in. For example, the variable a in the if block has a different internal name (identifier) from the variable a in the main function. The compiler will never mix them up.

Why you should always use var?

Because variable declaration and variable assignment shares the same syntax in Mojo, the compiler may not be able to distinguish your intention. If you always omit the var keyword when declaring a variable. This habit will lead to confusion and bugs, especially when you are working with nested scopes. See the following example, which would run without any error, but may produce unexpected results:

# src/basic/variables/unintended_reassignment_in_nested_scopes.mojo

def main():

var a = 1

if a == 1:

a = 2 # Reassign `a` to 2

# This `a` is the same variable as the outer `a`

# They both refer to the same address in memory

print("a=", a)

var b = 1

if b == 1:

var b = 2 # Create a new variable `b` in the local scope

# This `b` shadows the outer `b`

# They refer to different addresses in memory

print("b=", b)a= 2

b= 1In the first if block, we use a = 2. Since we did not use the var keyword, Mojo compiler thinks that we are re-assigning the value of the existing variable a in the parent scope. In this sense, no new variable is created, no new memory space is allocated. Mojo compiler simply changes the value of a in the parent scope to 2. Therefore, when we print a in the outer scope, it shows 2.

In the second if block, we use var b = 2. This tells Mojo compiler that we are creating a new variable b in the local scope. This new variable shadows the outer variable b, and Mojo compiler allocates a new memory space for it. Therefore, when we print b in the inner scope, it is 2. However, when we print b in the outer scope, it shows 1.

If you always omit the var keyword when declaring a variable, this habit will bring trouble to you. Let's say, you intend to create a new variable in the child scope, you use b = 2, and you think this is the correct way to create a new variable while keep the variable b in the parent scope unchanged. When you run the code, you will be surprised that the value b in the parent scope is changed to 2.

So, based on Yuhao's experience, it is always good to use the var keyword when declaring a variable. There are two main reasons:

- Explicitness: Using

varmakes it clear that you are declaring a new variable. It is particularly helpful when you are working on a large codebase or collaborating with others. You can easily identify where variables are declared and what their types are. It also allows you to put all variable declarations at the beginning of a function, which is a common practice in many programming languages. - Error prevention: Using

varhelps to prevent accidental overwriting of the values of variables in the parent scope, as shown in the example above.

Unused variables

In Mojo, if a variable is declared but not used, the compiler will issue a warning. This is to help you identify potential mistakes that you may have overlooked in your code. For example, the following code will generate a warning:

def main():

var a = "unused variable"warning: assignment to 'a' was never used; assign to '_' instead?

var a = "unused variable"

^In this case, we should consider removing this variable.

Another situation is when you do a loop over a list or a range, but do not use the loop variable. For example:

def main():

for i in range(5):

print("Hello, world!")You will get a warning like this:

warning: assignment to 'i' was never used; assign to '_' instead?

for i in range(5):

^

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Hello, world!In this case, you can use the underscore _ as a prefix to indicate that this variable is a temporary variable that you do not intend to explicitly use it. So the code can be rewritten as follows:

def main():

for _i in range(5):

print("Hello, world!")Major changes in this chapter

- 2025-06-18: Add some graphs for variables.

- 2025-06-21: Update to accommodate the changes in Mojo v25.4 (fcaa01b2).

- 2025-09-25: Update to accommodate the changes in Mojo v0.25.6.

Compilers like Cython and mypyc may use type hints for partial optimization. ↩︎